Samurai are legendary warriors and perhaps the most well-known class of people in ancient Japan. They were noble fighters that fought evil (and each other) with their swords and frightening armour. They followed a strict moral code that governed their entire life. The term samurai was originally used to denote the aristocratic warriors (bushi), but it came to apply to all the members of the warrior class that rose to power in the 12th century and dominated the Japanese government until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Samurai has been seen as a cultural representation of Japanese aestheticism and social values, and, more recently, a mythical symbol of heroic Japan, made immortal by the silver screen and Hollywood. That’s the popular idea, anyway. In reality, there’s so much more to the Samurai. We present you 10 fascinating facts about lives of Samurai. Enjoy the reading.

1. Female Samurai

While “samurai” is a strictly masculine term, the Japanese bushi class (the social class samurai came from) did feature women who received similar training in martial arts and strategy. These brave women were called “Onna-Bugeisha,” and they were known to participate in fights alongside their male counterparts. They were carrying naginata, a spear with a curved, sword-like blade that was versatile, yet relatively light.

Since historical texts offer relatively few accounts of these female warriors (the traditional role of a Japanese noblewoman was more of a homemaker), we used to assume they were just a tiny minority. However, recent research indicates that Japanese women participated in battles quite a lot more often than history books show. When remains from the site of the Battle of Senbon Matsubaru in 1580 were DNA-tested, 35 out of 105 bodies were female. Research on other sites has yielded similar results. Women power!

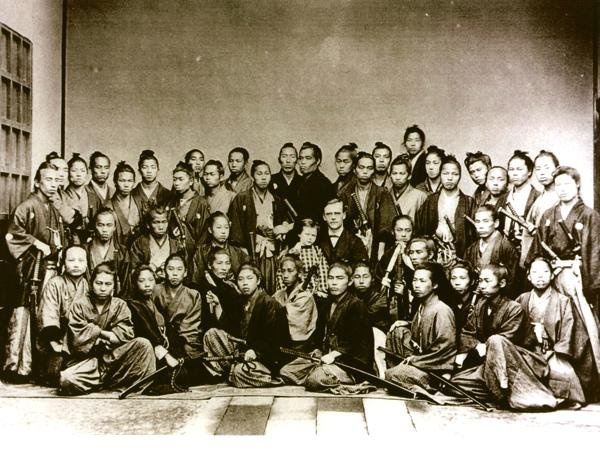

2. Western Samurai

Many of you have probably seen the movie The Last Samurai featuring Tom Cruise as a samurai. It’s true that under special circumstances, someone outside Japan could fight alongside the samurai, and even become one himself. This special honour (which included samurai weapons and a new, Japanese name) could only be bestowed by powerful leaders, such as daimyos (territorial lords) or the shogun (warlord) himself.

History knows four Western men who have been granted the dignity of the samurai: adventurer William Adams, his colleague Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn, Navy officer Eugene Collache, and arms dealer Edward Schnell. Out of the four, Adams was the first and the most influential: he served as a bannerman and advisor to the Shogun himself.

3. The Armour

The strangest thing about the samurai is probably their weird-looking, ornate armour. However, no part of it has been designed in such a way without a reason. The samurai armour, unlike the armour worn by European knights, was always designed for mobility. The armour was made of lacquered plates of either leather or metal, smartly bound together by laces of silk or leather. The arms were protected by large, rectangular shoulder shields and light, armoured sleeves. The right hand was often left without a sleeve to allow maximum movement. A good suit of armour had to be strong and sturdy, yet flexible enough to allow its wearer free movement in the battlefield.

The strangest and most convoluted part of the armour was the Kabuto helmet. Its bowl was made of riveted metal plates, while the face and brow were protected by a piece of armour that tied around behind the head and under the helmet. The most famous feature of the helmet was its Darth Vader–like neck guard (Darth Vader’s design was actually influenced by samurai helmets). It was so well-made and effective that the US Army actually based the first modern flak jackets on samurai armour. It defended the wearer from arrows and swords coming from all angles. Many helmets also featured ornaments and attachable pieces, including a moustachioed, demonic mengu mask that both protected the face and frightened the enemy. A leather cap worn underneath the helmet provided much-needed padding.

Although the samurai armour went through significant changes over time, its overall look always remained fairly consistent to the untrained eye.

4. Population

Many people think the samurai were either a scarce elite force or a small, tightly defined caste of noblemen. In reality, they were an entire social class. Originally, “samurai” meant “those who serve in close attendance to the nobility.” In time, the term evolved and became associated with the bushi class, middle- and upper-tier soldiers in particular.

This means there were quite a lot more of these mighty warriors than we generally assume. In fact, at the peak of their power, up to 10 per cent of Japan’s population was samurai (around 3.5% were samurai women). Because of their large numbers and long influence in Japan’s history, every single Japanese person living today is said to have at least some samurai blood in them.

5. The Fashion

Samurai were considered rock stars of their time and their style of clothing massively influenced the fashion of the era. Apart from the most formal occasions, samurai themselves didn’t dress to impress. Although their clothing was elaborate, every aspect of it was designed to fit their needs as warriors.

Samurai dressed for speed, travel, and freedom of movement. Their regular outfit consisted of wide hakama trousers and a kimono or a hitatare, a two-part vest with imposing shoulder points. The costume left the arms free, and the hitatare vest could quickly be removed in case of a surprise attack. The kimono was generally made of silk because of its coolness, feel, and appearance. For footwear, either wooden clogs or sandals were used.

The most distinctive part of samurai fashion, the topknot hairstyle, was also the most widespread. Except for Buddhist monks (who shave their heads), people of all social classes wore the topknot hairstyle for hundreds of years. The habit of combining the topknot with a partially shaved head was developed out of necessity: The shaved forehead made it more comfortable to wear a helmet.

6. Homosexuality

Not many people know that samurai were extremely open-minded when it comes to sexual relations. Much like the Greek Spartans, another warrior culture, the samurai not only accepted the presence of same-sex relations in their culture—they actively encouraged them. These relationships were generally formed between an experienced samurai and a youth he was training (again, very much like the Spartans). The practice was known as wakashudo (“the way of the youth”), and it was reportedly done by all members of the class. In fact, wakashudo was such a common thing that a daimyo might have faced some embarrassing questions if he didn’t engage in it.

Not many people know that samurai were extremely open-minded when it comes to sexual relations. Much like the Greek Spartans, another warrior culture, the samurai not only accepted the presence of same-sex relations in their culture—they actively encouraged them. These relationships were generally formed between an experienced samurai and a youth he was training (again, very much like the Spartans). The practice was known as wakashudo (“the way of the youth”), and it was reportedly done by all members of the class. In fact, wakashudo was such a common thing that a daimyo might have faced some embarrassing questions if he didn’t engage in it.

Although wakashudo was considered a fundamental aspect of the way of the samurai, history has kept relatively quiet about it. Pop culture depictions of samurai, ushered in by director Akira Kurosawa and his trusted actor Toshiro Mifune, have never addressed this fact either.

7. Harakiri / Seppuku

One of the most terrifying things about the way of the samurai is seppuku (also known as “hara-kiri”). It is the gruesome suicide a samurai must perform if he fails to follow bushido or is likely to be captured by the enemy. Seppuku could be either a voluntary act or a punishment. Either way, it has been generally seen as an extremely honourable way to die.

Most people are familiar with the “battlefield” version of seppuku, which is a quick and messy affair. It is performed by piercing the stomach with a short blade and moving it from left to right, until the performer has sliced himself open and essentially disembowelled himself. At this point, an attendant—usually a friend of the samurai—decapitates the disembowelled samurai with a sword (otherwise, dying would be an extremely long and painful process). However, the full-length seppuku is a far more elaborate process.

Formal seppuku is a long ritual that starts with ceremonial bathing. Then, the samurai is dressed in white robes and given his favourite meal (much like the last meal of death row prisoners). After he has finished eating, a blade will be placed on his empty plate. He will then write a death poem, a traditional tanka text where he expresses his final words. After the poem is finished, he grabs the blade, wraps a cloth around it (so it won’t cut his hand), and does the deed. Again, the attendant finishes him by cutting his head off. However, he aims to leave a small strip of flesh in the front so that the head will fall forward and remain in the dead samurai’s embrace. This is also so that the head will not accidentally fly at the spectators, which would cause the attendant eternal shame.

8. The Weapon

As soldiers, samurai employed a number of different weapons. The Samurai’s weapon was yet another important aspect of his life, most notably their Katana sword; although, the Samurai wore two swords, a wakizashi and a katana. Their swords were made by master swordsmiths and quality tested on the corpses of criminals.

They originally carried a sword called a “chokuto,” which was essentially a slimmer, smaller version of the straight swords later used by medieval knights.

As sword-making techniques progressed, the samurai switched to curved swords, which eventually evolved into the katana. The katana is perhaps the most famous sword type in the world. Certainly the most iconic of all samurai weapons. Bushido (the samurai code) dictated that a samurai’s soul was in his katana, which made it the most important weapon he carried. Katanas were usually carried with a smaller blade in a pair called “daisho,” which was a status symbol used exclusively by the samurai class. Implements like the jutte and kusurigama allowed users to defend and combat the katana. Fans, smoking pipes and other weapons disguised as everyday items meant one had to be wary at all times. Other weapons, like rocket launchers, seem more fit for manga than actual battlefields.

They also commonly used the yumi, a longbow they practised religiously with. Spears became important as personal bravery on the battlefield was eventually replaced by meticulous planning and tactics. When gunpowder was introduced in the 16th century, the samurai abandoned their bows in favour of firearms and cannons. Their long-distance weapon of choice was the tanegashima, a flintlock rifle that became popular among Edo-era samurai and their footmen.

9. Physical Traits

The imposing armour and weaponry make samurai seem gigantic. They’re often depicted as quite large and well-built in pop culture. However, if you’ve ever been to any part of Asia, you know that Asians are quite short. Most samurai were quite tiny—a 16th-century samurai was usually very slim and ranging from 160 to 165 centimetres (5’3″ to 5’5″) in height. For comparison, European knights of the same period probably ranged from 180 to 196 centimetres (6′ to 6’5″).

What’s more, the noble samurai might not have been as “pure” as the notoriously race-conscious Japanese would like. Compared to the average Japanese person, members of the samurai class were noticeably hairier and their skin was lighter. Their profile—namely, the bridge of their nose—was also distinctly more European. In an ironic twist, this seems to indicate that the samurai actually descend from an ethnic group called the Ainu, who are considered inferior by the Japanese and are often the subject of discrimination.

Many of the Samurai were women: Japan’s Female Samurai Who Feared Nothing: Onna-Bugeisha

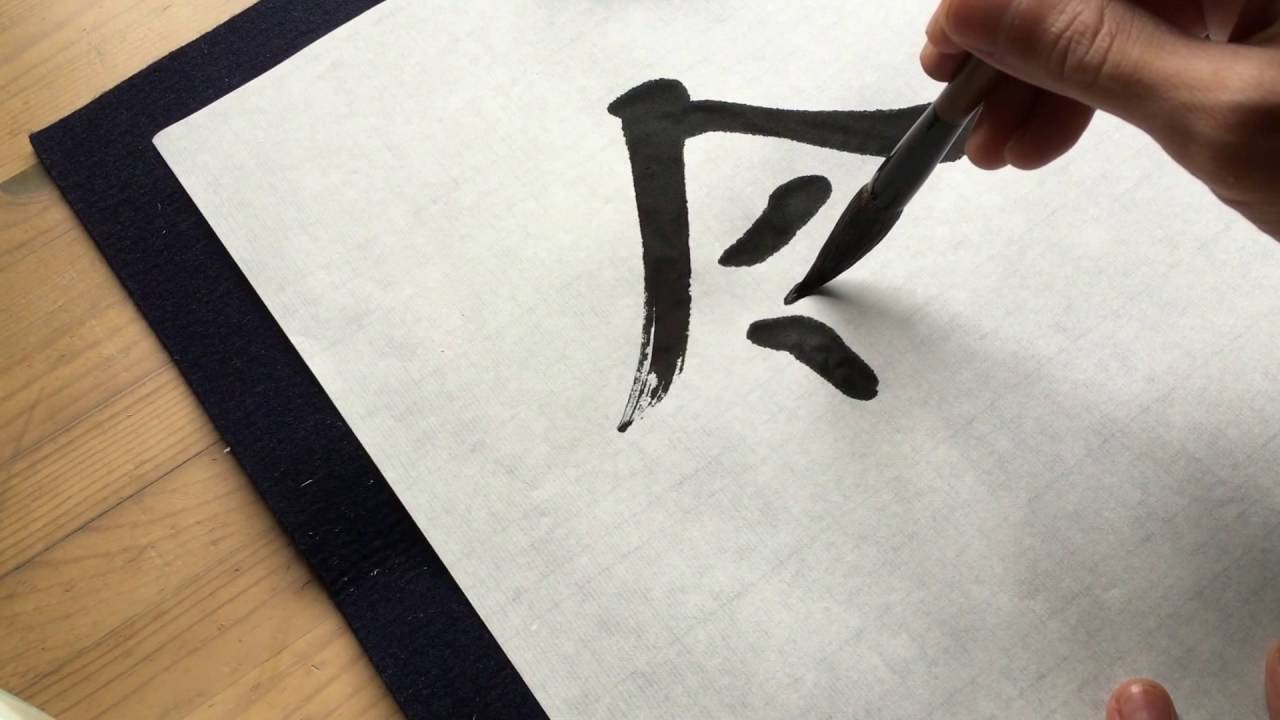

10. Education

Bushido dictated that a samurai strives to better himself in a multitude of ways, including those unrelated to combat. This is why the samurai class participated in a number of cultural and artistic endeavours. Poetry, rock gardens, monochrome ink paintings, and the tea ceremony were common aspects of samurai culture. They also studied subjects such as calligraphy, literature, and flower arranging. Similarly, female samurai were striving to become excellent homemakers, artists and warriors.