There’s a moment, right after you unwrap a Japanese kitchen knife for the first time, when you just hold it. You tilt it under the light. You notice the texture on the blade — those irregular dimples, those rippling waves of steel — and something clicks. This isn’t a tool that rolled off a factory line. Someone made this. Someone hammered it.

But here’s the thing most knife articles won’t tell you: those finishes aren’t decoration. They’re functional choices made by blacksmiths who’ve been refining their craft for generations. And understanding what they do — what they actually do when you’re chopping onions at 7pm on a Wednesday — makes a real difference in how you use and care for your knife.

So let’s talk about the main Japanese blade finishes. What they mean, how they’re made, and why they matter once the knife is in your hand.

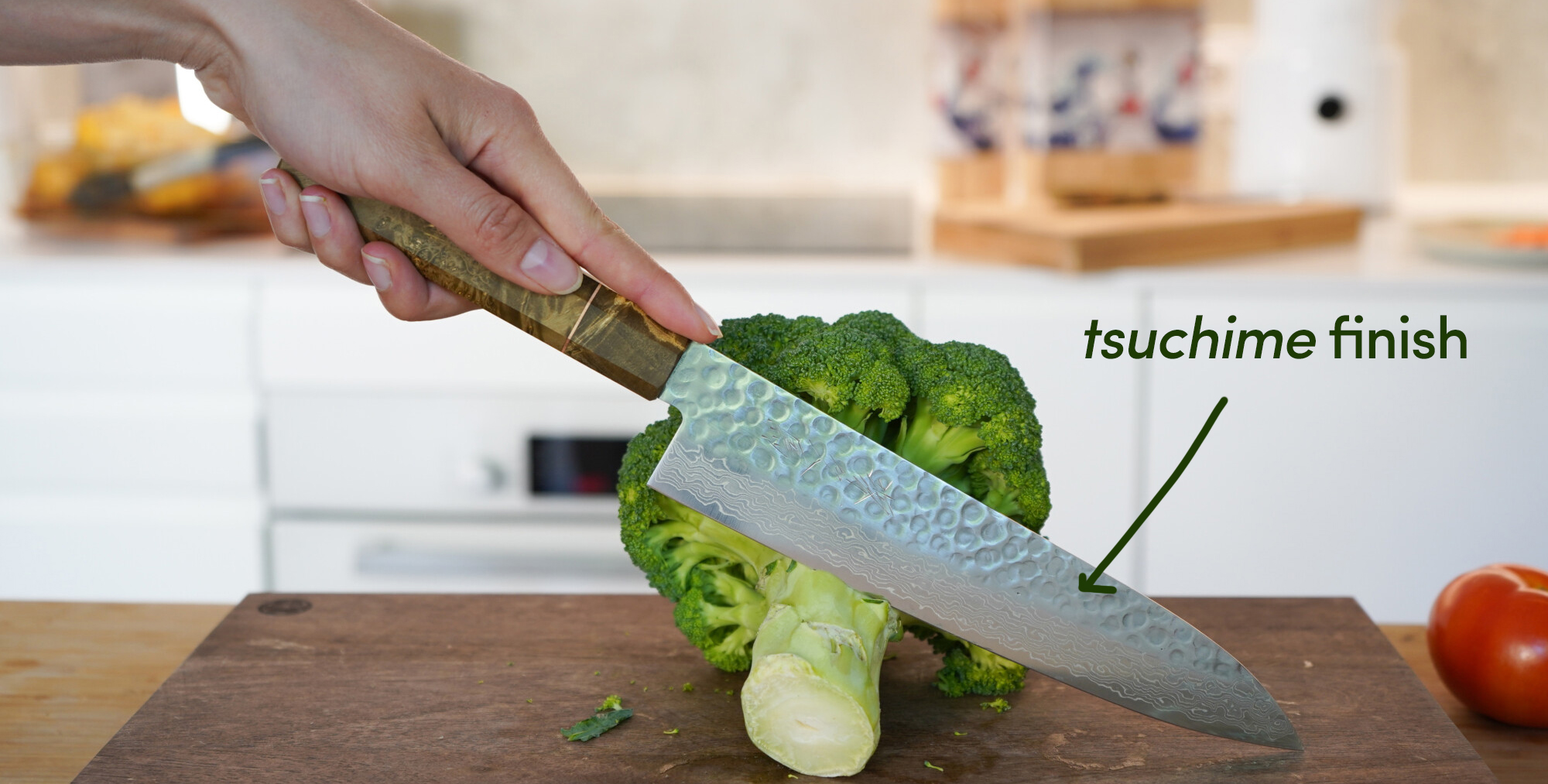

Tsuchime: The Hammered Finish

Tsuchime (槌目) translates literally to “hammer mark.” The name is about as straightforward as Japanese craft terminology gets. A blacksmith takes the blade and strikes it repeatedly with a hammer, creating a pattern of irregular indentations across the surface. Each strike is deliberate but not uniform — and that’s the whole point.

The technique has roots in traditional Japanese metalwork that extends well beyond kitchen knives. Blacksmiths in regions like Seki (in Gifu Prefecture) and Sakai (near Osaka) have passed these methods down through apprenticeships that span decades. When we say the blades in our Seki Kyuba lines are handcrafted by skilled blacksmiths in Seki, we mean exactly that — individual artisans doing work that can’t be replicated by a machine, because the irregularity is what makes it work.

What tsuchime actually does in the kitchen

The practical benefit comes down to food release. Those little pockets created by the hammer strikes trap tiny air cushions between the blade and whatever you’re cutting. When you slice through a potato or a cucumber, the food doesn’t suction onto the flat of the blade. It falls away. Anyone who’s spent time peeling thin slices of sweet potato off a flat Western knife knows how annoying that suction effect can be.

Our KYU line — the Sakai Kyuba range handmade in Sakai — features a tsuchime finish on the upper part of the blade, combined with 46 layers of Damascus cladding. The hammered texture sits above the cutting edge, right where food tends to stick most during prep work. It’s a practical decision, not an aesthetic afterthought.

The KATA line uses the same tsuchime approach across its VG10 core and 3-layer construction. On the KATA Bunka, for instance, the hammered finish runs along the blade’s flat, creating those air pockets where they matter most — between your knife and the ingredient. The Nakiri in the KATA range benefits from this perhaps more than any other shape, because a nakiri’s entire purpose is repetitive push-cutting through vegetables. Anything that reduces sticking makes that task noticeably smoother.

The look of tsuchime

There’s no getting around it: tsuchime looks beautiful. Each blade carries a slightly different pattern because each was hammered by hand. Two KATA Santoku knives will perform identically, but if you look closely, their hammer marks will differ. That kind of individuality used to be the norm for all tools — before mass production made everything identical. There’s something satisfying about owning a knife that’s genuinely one of a kind, even if you can’t quite articulate why.

Damascus: Layers With a Purpose

Damascus steel has become something of a buzzword in the knife world, and it deserves better than that. The Damascus patterns you see on Japanese kitchen knives are created by folding and forging multiple layers of different steels together. When the blade is etched or polished, the contrasting metals reveal flowing, wave-like patterns across the surface.

But Damascus isn’t just about looking impressive on a kitchen counter. The layering process serves real engineering functions.

How layered construction works

Take the RYU line as an example. Each RYU blade has a VG10 steel core — that’s the hard, sharp cutting edge — wrapped in 33 layers of Damascus cladding. The core steel does the cutting. The surrounding layers protect it. They add structural integrity to the blade, help with corrosion resistance, and absorb shock during heavy use. Think of it like reinforced concrete: the steel rebar (VG10 core) provides strength, while the concrete (Damascus layers) gives it mass and resilience.

The RYU Gyuto, with its 21cm blade, shows this construction at its best. The full Damascus pattern runs the length of the blade, and the 33 layers create a visible flowing effect that’s different on every single knife. When combined with the hammered tsuchime finish that sits on top of the Damascus, you get both the air-pocket food release and the structural benefits of multi-layer forging.

Our SHIN line takes this further with 31 layers of Damascus wrapped around an SG2/R2 powdered steel core. SG2 is a step above VG10 — it’s harder, holds an edge longer, and is made through a powder metallurgy process that produces a finer, more consistent grain structure. The Damascus cladding around that SG2 core isn’t just decorative protection. At 63-64 HRC (Rockwell Hardness), the SHIN’s core steel is extremely hard, which means it can be somewhat more brittle. The softer Damascus layers act as a buffer, absorbing impacts that might otherwise chip the cutting edge.

The NIJI approach: Damascus reimagined

Then there’s our NIJI line, which takes Damascus in a completely different direction. Instead of using only layers of stainless steel, the NIJI blades feature a 12Cr18MoV steel core sandwiched between 37 layers of stainless steel, brass, and copper. The result is a blade that catches light differently depending on the angle — warm copper tones mixing with cool steel, creating patterns that genuinely resemble a rainbow. (NIJI means “rainbow” in Japanese, so the name isn’t subtle about it.)

What makes NIJI interesting from a technical standpoint is that the mixed metals aren’t randomly chosen. Copper and brass have different expansion rates and hardness properties than stainless steel. When forged together, they create a blade with unique vibration-dampening characteristics. The cutting performance sits just below the SHIN line, but the visual effect is in a category of its own.

Migaki, Kasumi, and Kurouchi: Other Finishes Worth Knowing

Tsuchime and Damascus get the most attention, but they’re not the whole picture. Japanese bladesmiths use several other finishing techniques, and understanding them helps you appreciate why certain knives look and feel the way they do.

Migaki (磨き) is a mirror polish. The blade is ground and polished until it’s reflective. You’ll see this on high-end sushi knives primarily. It looks stunning, but it’s a maintenance commitment — fingerprints, water spots, and micro-scratches show up immediately. Migaki finishes also offer zero food release benefit, which is why you rarely see them on home cooking knives.

Kasumi (霞) means “mist” and refers to the hazy contrast between a hard core steel and softer cladding. When a blade is sharpened and polished, the two different steels take on different appearances — the cutting edge is bright and clear, while the cladding has a cloudy, matte look. This is visible on our KATA knives where the VG10 core steel is visible against the softer outer layers. It’s a subtler effect than Damascus, but it tells you something important: you can see exactly where the hard cutting steel ends and the protective cladding begins.

Kurouchi (黒打ち) translates to “black forging” and refers to the dark, rough oxide layer left on a blade after forging. Rather than polishing it away, the blacksmith leaves it as-is. It’s the rawest, most rustic finish — and it’s completely functional. The oxide layer acts as a natural non-stick surface and provides corrosion resistance. You won’t find kurouchi on our knives (our lines use more refined finishing techniques), but it’s worth knowing about because it represents the other end of the spectrum from migaki: maximum function, minimum fuss.

Why the Finish Matters for Maintenance

Different finishes don’t just affect performance — they affect how you care for your knife, and that’s worth thinking about before you buy.

A tsuchime finish, like on our KYU and KATA lines, is relatively forgiving. The textured surface hides minor scratches and patina development. You don’t need to baby it. Wash it by hand, dry it, and you’re done. The hammered texture actually ages well — over time, it develops a character that smooth blades simply don’t have.

Damascus finishes require slightly more attention if you want to keep the pattern vivid. The contrast between layers can fade if the blade develops a uniform patina. A periodic wipe with a food-safe mineral oil keeps things looking sharp (pun intended, apologies). On our RYU and SHIN lines, the combination of Damascus with tsuchime gives you some visual insurance — even if the Damascus contrast mellows over time, the hammered texture remains.

The NIJI’s multi-metal Damascus is the most visually dramatic, and also the most responsive to care. The copper and brass layers can develop their own unique patina over time, which some owners love and others prefer to polish away. Either approach is fine — it’s your knife.

The Blade Shapes: A Quick Note

Since we’re talking about blade techniques, it’s worth touching briefly on how these finishes interact with different knife shapes in our range.

The Gyuto (available in our RYU and SHIN lines) has a gentle curve along its cutting edge. On a 21cm or 24cm blade, the Damascus pattern flows beautifully along that curve. The longer blade gives the pattern more room to breathe, which is part of why the Gyuto is often the showpiece of a collection.

The Santoku (in our KATA and SHIN lines) has a shorter, wider blade with less curve. The tsuchime finish is particularly effective here because the santoku’s flat profile means more blade surface comes in contact with your cutting board — and with your food. More contact surface means more potential for sticking, which means those hammer marks work harder.

The Nakiri takes this even further. Its completely flat edge and tall, rectangular profile are designed for straight push-cuts through vegetables. Every millimetre of that blade contacts the ingredient. The tsuchime finish on our KATA Nakiri and RYU Nakiri is arguably more functionally important here than on any other knife shape.

The Kiritsuke (SHIN line only) combines a gyuto’s versatility with a more angular tip. It’s traditionally a knife reserved for head chefs in Japanese kitchens — a status symbol as much as a tool. The 31-layer Damascus on the SHIN Kiritsuke makes a visual statement that matches the knife’s cultural significance.

And the Petty — our smallest blade at 12cm (KATA) or 15cm (RYU) — proves that even a compact knife benefits from proper finishing. The tsuchime and Damascus on our petty knives make detailed work like trimming and peeling noticeably less fussy, because small pieces of food are even more prone to sticking.

Seki and Sakai: Two Cities, Two Traditions

Our knives come from two historic knife-making centres in Japan, and the distinction matters.

Sakai, near Osaka, has been producing blades for over 600 years. It’s where our Sakai Kyuba KYU line is made. Sakai’s tradition is rooted in crafting single-bevel knives for professional sushi chefs — a heritage of extreme precision. The KYU line carries that DNA into a more accessible format, with AUS10 steel and 46-layer Damascus cladding at a price point that makes genuine Japanese craftsmanship available to home cooks who are just beginning to explore what a proper knife can do.

Seki, in Gifu Prefecture, is sometimes called the “City of Blades.” It has an 800-year history of sword and knife making and is where our KATA, RYU, SHIN, PAN, and NIJI lines are produced. Seki’s tradition leans toward innovation — the blacksmiths there have been early adopters of modern steels like VG10 and SG2 while maintaining traditional forging and finishing techniques. The combination of tsuchime, Damascus, and advanced steel in our Seki Kyuba lines is a direct product of that forward-looking mentality.

Both cities take the craft seriously in a way that’s difficult to overstate. These aren’t marketing stories — they’re places where young apprentices still spend years learning to hammer a blade before they’re allowed to finish one.

Choosing Based on What Matters to You

If you’re reading this trying to figure out which knife to buy, here’s a practical framework.

If you want the best food release during prep and you’re not especially bothered about elaborate blade patterns, the tsuchime finish on the KATA line gives you that at a very reasonable price, with VG10 steel that holds an edge well and sharpens easily.

If the visual character of your knife matters to you — if you want something that feels like an object worth owning, not just using — the full Damascus of the RYU line adds that dimension without a dramatic price jump.

If you want the absolute best edge retention and you’re willing to invest in a knife you’ll use for decades, the SHIN line’s SG2 steel with 31-layer Damascus is as good as kitchen cutlery gets.

And if you want something that’s going to make people stop and ask about your knife every single time you cook for guests, the NIJI’s rainbow Damascus is hard to beat.

Whatever you choose, the finish on your blade isn’t a gimmick. It’s the product of centuries of refinement by people who understood that how a tool feels in your hand matters just as much as how it performs. That’s something worth appreciating, even at 7pm on a Wednesday.