The Japanese island of Okinawa nicknamed the Village of Longevity has residents with the highest life expectancy in the world. They also largely share a devotion to a Japanese philosophy known as ikigai (pronounced Ick-ee-guy), translated in a simple meaning as the happiness derived from being busy at some activity that holds meaning and purpose for them.

Ogimi, the friendly village of 3,000 of the world’s longest-living people, is known for its slow pace, ocean views, community gatherings, personal vegetable gardens and residents who smile, laugh and joke incessantly. They also take great pride in living to 100 and beyond. They have fewer chronic illnesses than most people, including cancer and heart disease, and their rate of dementia is well below the global average.

Blue zones

The concept of ikigai seems to be a very attractive but the full answer to a happy and long life is probably a combination of factors that include the usual suspects: diet, movement/exercise and having friends and community. What these “blue zone” (as according to Dan Buettner, the author of Blue Zones: Lessons on Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the Longest) areas of longevity and happiness around the world have in common are residents who curate a simple life with few possessions, plenty of time outdoors, staying active with friends, getting enough sleep, and eating lightly and healthily.

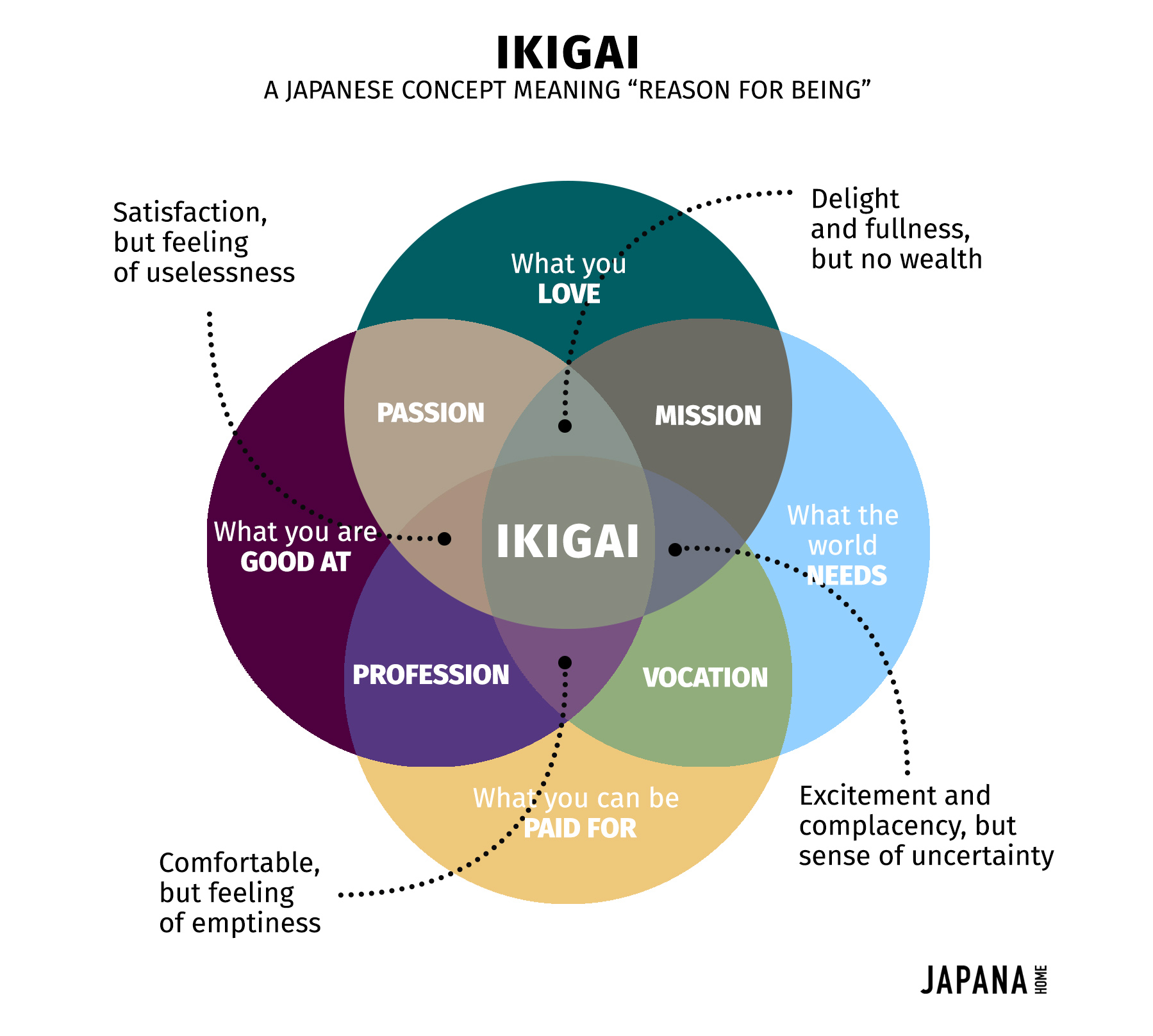

Japanese take the concept of ikigai very close to their heart. To understand what an ikigai is you need to make three lists: your values, things you like to do, and things you are good at. The cross section of the three lists is your ikigai.

Studies show that losing one’s purpose can have a detrimental effect. Your ikigai is at the intersection of what you are good at and what you love doing.

Since the dawn of time, some humans have lusted after objects and money only to feel dissatisfaction at the relentless pursuit of it, and instead focus on something bigger than their own material wealth. This has over the years been described using many different words and concepts, but it always came down to seeking the central core of meaningfulness in life.

Ikigai is seen as the convergence of four primary elements:

- What you love (your passion)

- What the world needs (your mission)

- What you are good at (your vocation)

- What you can get paid for (your profession)

Discovering your own ikigai is said to bring fulfilment, happiness and make you live longer.

How to find your Ikigai

To find your Ikigai you need to ask yourself the following four questions:

- What do I love?

- What am I good at?

- What can I be paid for now — or something that could transform into my future hustle?

- What does the world need?

10 rules to help find your Ikigai

In their book Ikigai The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life, Hector Garcia and Francesc Miralles break down the ten rules that can help anyone find their own ikigai.

- Stay active and don’t retire

- Leave urgency behind and adopt a slower pace of life

- Only eat until you are 80 per cent full

- Surround yourself with good friends

- Get in shape through daily, gentle exercise

- Smile and acknowledge people around you

- Reconnect with the nature

- Be grateful for everything, especially things that brightens our day and makes you feel alive

- Live in the moment

- Follow your ikigai

Follow your curiosity

When we’re children, we wander and are constantly curious about world that surrounds us. As we grow, we put ourselves in roles that we think we ought to play and restrain ourselves from being curious. The problem for millions of people is that they stop being curious about new experiences as they assume responsibilities and build routines.

We are born wild and curious. Our insatiable drive to learn, invent, explore, and study deserves to have the same status as every other drive in our lives. Fulfilment is fast becoming the main priority for most of us. Millions of people still struggle to find what they are meant to do. What excites them. What makes them lose the sense of time. What brings out the best in them.

Albert Einstein once said:

Don’t think about why you question, simply don’t stop questioning. Don’t worry about what you can’t answer, and don’t try to explain what you can’t know. Curiosity is its own reason. Aren’t you in awe when you contemplate the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure behind reality? And this is the miracle of the human mind — to use its constructions, concepts, and formulas as tools to explain what man sees, feels and touches. Try to comprehend a little more each day. Have holy curiosity.