A bit of a knife history…

The city of Sakai is situated by the Osaka bay in Japan’s main island. The foundations for knife making were laid down as early as the fifth century AD. That is when the great mounds, the Kofun, were built. This required excellent tools, which were manufactured by local craftsmen.

During the 14th century, Sakai became the capital of the samurai sword making.

The city kept its position during the centuries to come. In the late 16th century they started making knives according to the same methods as the famous Sakana swords. The knife making was a result of the Portuguese introduction of tobacco in Japan. The demand for quality knives to cut the tobacco exploded. The first tobacco knives were made in Sakai, and were soon renowned in Japan for their unique sharpness.

The art of blade-making has been popular for a long time in Japan. But it was only in the 16th century that the trend of manufacturing highly specialised cooking knives became widespread. This occurred because blacksmiths working for members of Japan’s noble soldier class (the Samurai) competed to create the best swords and knives.

Knives and cooking

Eventually, as different regional cuisines began to develop across Japan, merchants from different regions began learning the craft. In the east, where more-rustic cooking methods reigned, stout and functional straight blades were predominant; in the west, more-delicate, pointed styles found favour. Sakai makes the best hand-forged Japanese knives. The most commonly used types in the Japanese kitchen are:

- the deba bocho (fish filleting),

- the santoku hocho (all-purpose utility knife)

- the nakiri bocho and

- usuba hocho (Japanese vegetable knives) and

- the takohiki andyanagiba(sashimi slicers).

Most knives are referred to as hōchō (包丁), or bōchō (due to rendaku), but sometimes have other names, like -Kiri (〜切り, “cutter”). There are two classes of traditional Japanese knife forging methods: honyaki (mono steel) and Kasumi. The class is based on the method and material(s) used in forging the knife.

Honyaki forging

Honyaki knives are forged from one material. This is generally top-grade knife-specific steel.

Kasumi forging

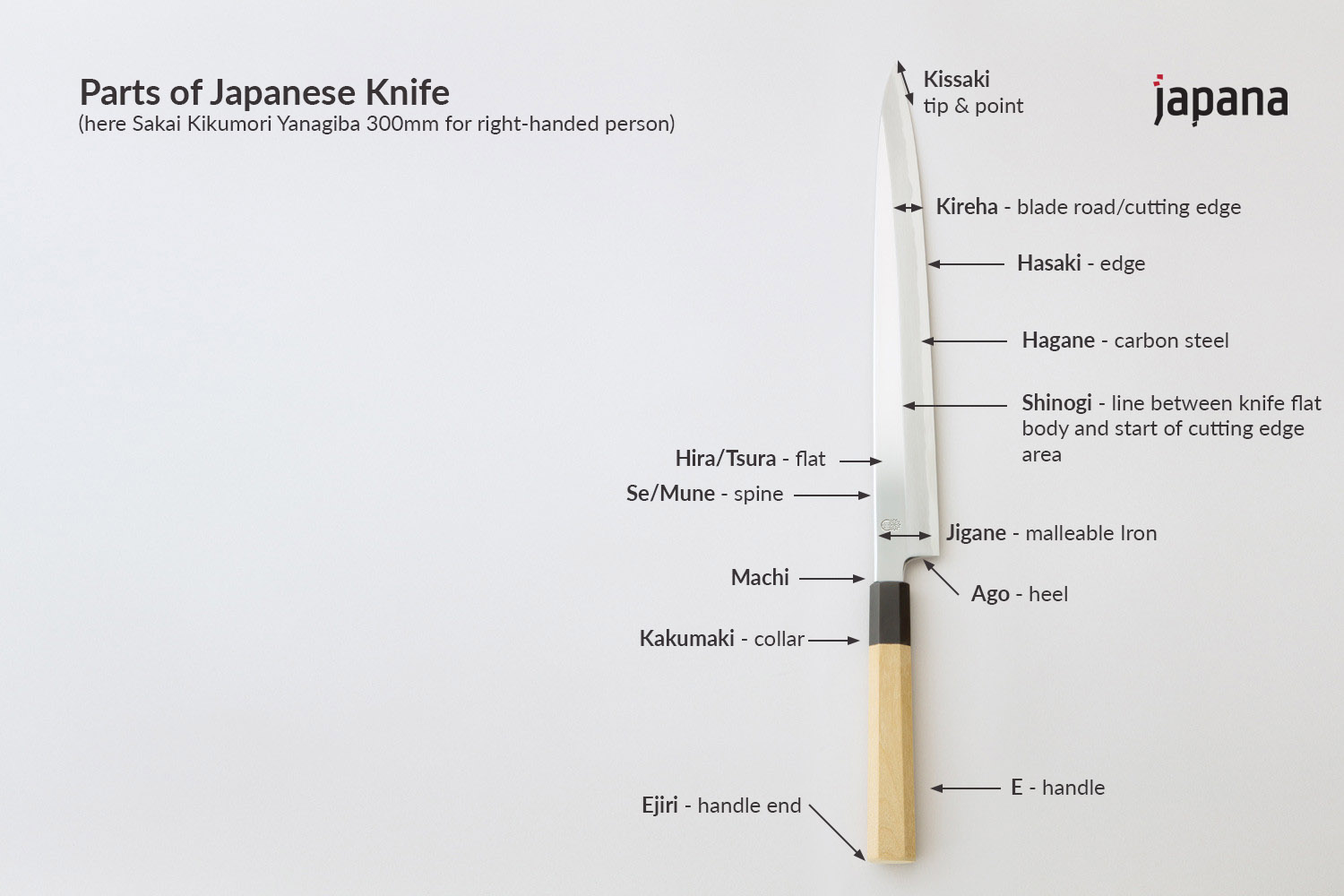

Kasumi is made from two (or more layers of) materials: “hagane” (hard brittle cutting steel) and soft iron “jigane” (protective steel) welded together. This style of knife offers a similar cutting edge to a honyaki blade. It also offers the benefit of being “more forgiving” and generally easier to maintain than the honyaki style, at the expense of the steels brittle nature. Some see this as an advantage. Kasumi-forged knives are especially good for first-time knife buyers and occasional cooks.

San Mai

San Mai (three layers) generally refers to knives with the hard steel hagane (over 50 different carbon and stainless steels are used by Japanese knife makers) in forming the blade’s cutting edge and jigane (soft pliable steels) forming protective jacket on both sides of brittle hagane steel. In stainless versions, this offers a practical and visible styling known as “Suminagashi” (not to be confused with Damascus Steel). Suminagashi provides an advantage of a superb cutting edge, with a corrosion resistant exterior. In professional Japanese kitchens, the edge is kept free of corrosion (when carbon steel is used for the Hagane) and knives are generally sharpened on a daily basis (which can limit the life of a knife to less than three years).

Originally, all Japanese kitchen knives were made from the same carbon steel as the traditional Japanese swords named Nihonto but the forging method is different. Nihonto is forged out of one type of steel that is laminated and then differentially heat treated. Currently, san mai (hagane and jigane) knives have similar quality, containing an inner core of hard and brittle carbon steel, with a thick layer of soft and more ductile steel layered to the core (hagane) so that the hard steel is exposed only at the cutting edge.